Issue #2: Thoughts on ventures (and non-ventures)

Also: blogging to find interesting people, learning macroeconomics, and analyzing countries' geographical constraints

Table of content

Curations of the week:

A blog post is a very long and complex search query to find fascinating people and make them route interesting stuff to your inbox

How to create your own VC fund out of a newsletter

Fewer businesses than you think is actually venture-backable

How to trick investors and VCs

Learning macroeconomics and monetary policy

Geographical analysis of Brazil

Curiosities of the week:

Hot takes

Open questions

Books / papers

Graphs / charts / tables / maps

Reach out to me if you have interesting topics to discuss / have interesting references

Curations of the week

A blog post is a very long and complex search query to find fascinating people and make them route interesting stuff to your inbox

The post above sums up nicely on my intention why I write. My interests are getting increasingly niche and idiosyncratic, hence finding like-minded folks are getting harder.

People do things like coffee chats etc. But these are capacity-constrained and are synchronous (finding common time to meet with 2 weeks lead time?). There’s only so many coffee chats you can do with limited time here. In addition, most MBAs think alike, even here (LOL hot take). Not a lot of coffee chats surprise me with new information anymore.

Writing is good because it is scalable (write once and reach however many people), lets you diversify the audience base (more interesting pool of people), and asynchronous (thought pieces from several years ago are being found out by people). Bonus: my wife evaluated my marriage proposal based on quality of my writing and it did convince her. So this has worked really well for me.

How to create your own VC fund out of a newsletter

I stumbled on on this newsletter a couple of months ago.

A subscriber gave me a link to another newsletter that breaks down growth strategy of interesting newsletters (immediate application of above principle: getting people to route interesting stuffs to your inbox!) - How Packy McCormick Makes $3.5 Million with 180k Subscribers. What Packy did in his newsletter:

Sponsored deep dive on companies ($20K fees!)

Job board (because the write-ups attracted high quality people that can endure 5K+ words worth of content)

VC investing (because your deep dives are your due diligences, and you ends up knowing people who are willing to co-invest with you)

There’s a lot of people trying to “break into VC”, doing all sort of work to pass the gatekeepers (I heard people are encouraged to differentiate themselves from the sea of cold emails by bringing deals to those VCs). Packy just did his own VC work by himself, nobody is stopping him from analyzing companies, convincing would-be LPs, and invest in those companies. A reminder that there are many ways to reach your goal, even by skipping those gatekeepers. You only need high agency.

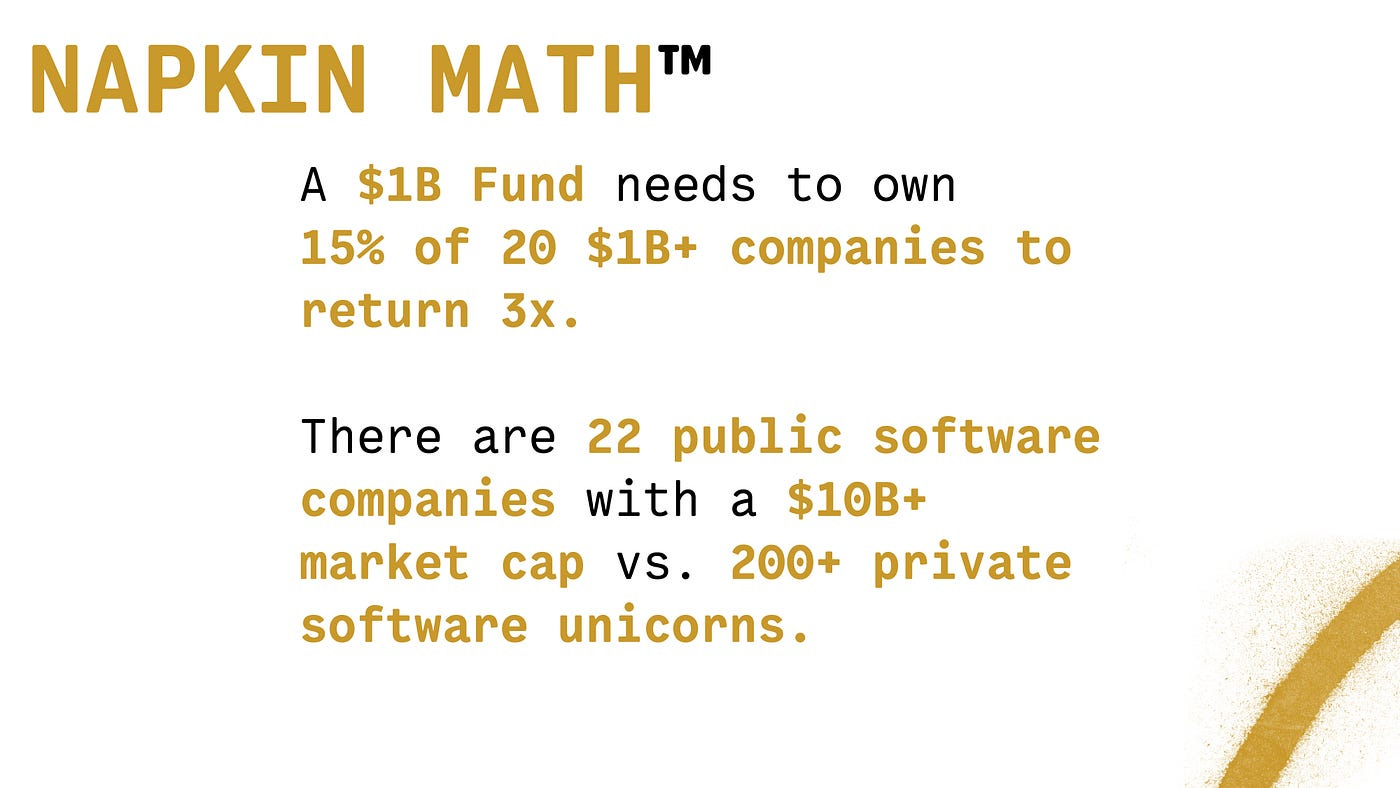

Fewer businesses than you think is actually venture-backable

We’re Selling Entrepreneurship Short

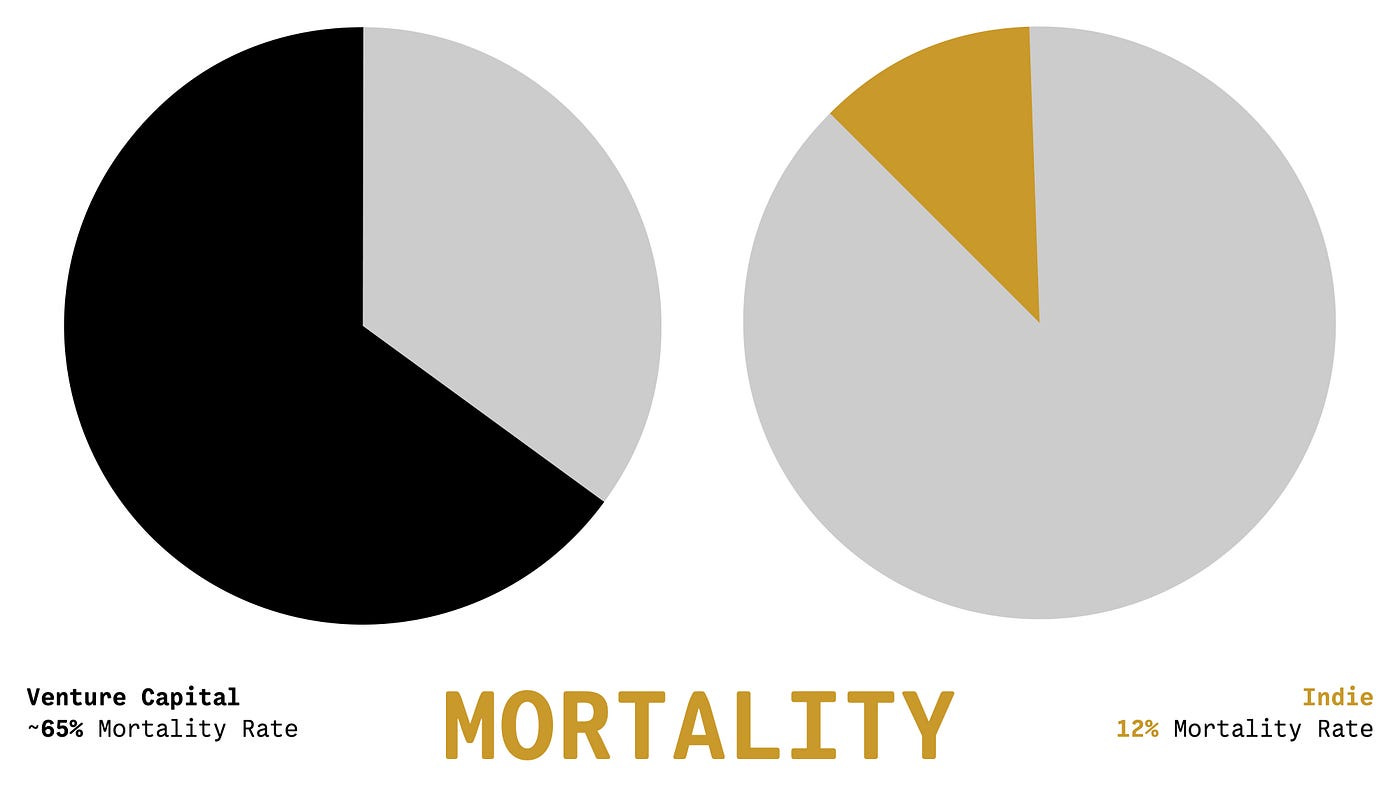

It’s actually hard to live up to your valuation. Going indie means that you are 5x less likely to die vs venture-backed companies.

The Silicon Valley small business, the SV-SB, is a hybrid of sorts — it intertwines small business values and discipline with big tech know-how and ambition.

Founding teams may look like that of a “traditional” Silicon Valley startup. They’re native to Silicon Valley ethos, skills, and playbooks. But, beneath the surface, they’re different. You might see more solopreneurs and studios (and LLCs instead of C-corps). They value autonomy and flexibility. They envision a range of potentially good outcomes — not binary, all-or-nothing scenarios.

Teams stay small and run fast for as long as they can. I define a Silicon Valley small business as having 20 or fewer employees (and often less than 10). In my experience, startup teams above this size are forced to operate very differently — much slower, with more bureaucracy, and less alignment. But below the threshold, a savvy team can create leverage and punch above its size.

They’re growth-oriented and going for efficient scale. Unlike small businesses (and contrary to the common characterization of teams that bootstrap), SV-SBs aren’t just trying to build “lifestyle” businesses or modest passive income streams. They want to scale, as quickly and efficiently as possible. The desire and often the know-how to scale separates them from traditional small businesses, and their focus on doing it leaner and profitably can separate them from the traditional SV startup.

They try to bootstrap to profitability instead of relying on venture capital. They’re VC-literate yet aren’t charmed by the potential status, signal, or stability. Perhaps they raise the equivalent of a friends & family or pre-seed round but not much more. They look for capital-efficient businesses and prioritize profit alongside growth early on. With less money going in, there’s a lower bar for financial return. Moreover, “success” doesn’t require a billion dollar exit. Making millions is a win (and thousands keeps the team afloat).

Some practical tips on operational implication of choosing staying as a bootstrapped company / “indie”:

How to trick investors and VCs

Useful accounting knowledge below. Also: any lessons on “dark arts” can be thought to be lessons on “defense against dark arts”, and vice versa.

VCs are smart people, but they are often easier to trick (especially at the earlier stages) than public market investors for a few reasons:

Company management controls the narrative and what is reported to VCs. Definitions can be loose and changed because they aren’t in the public eye.

Lots of VCs today don’t have a finance background. Many are founders and operators turned VC who don’t have deep accounting/finance knowledge.

Many VCs don’t dig that deep. The focus is on the topline and they assume that everything else will work itself out.

Learning macroeconomics and monetary policy

After some classes in BGIE (Business, Government, and the International Economy) and seeing how monetary policy and macroeconomics can screw entire countries and generations, I am very motivated to learn more.

I found this person working on Global Macro Hedge Fund from Wall Street Oasis forum last year, and he seems to be young but really knowledgeable. 1st Year Macro HF Analyst: My Macro Framework. Example Substack post below (it looked very dry to me last year, but now it all makes sense. Amazing how even very little prerequisite understanding unblock whole body of new knowedge) :

I am still looking for a good books about macro, so let me know if you have good ones.

Geographical analysis of Brazil

I read Guns, Germs and Steel back in 3rd year of undergraduate, but as time passes, I don’t like the line of thinking behind “geographical determinism”. That being said, I still feel we should understand a country’s unique geographical constraints so we are informed in charting the way forward. Example interesting analysis on Brazil below (really curious how it will pan out for Indonesia):

Rivers are not that useful in Brazil:

The Amazon is the only navigable river, but as we saw it only serves a few million people, and less than 10% of the Brazilian GDP.

The Paraná, Paraguay rivers (green in the south in the river basin map above, because they both merge into the Rio de la Plata in Argentina) and the Uruguay river (purple, at the bottom) are all navigable, but not in the Brazilian portions.

The coast has a bunch of small rivers that go through rugged terrain. They are not navigable.

Instead, most of the water close to the coast flows inland! That creates big river basins like those of the São Francisco river, but because the terrain is so rugged, none are navigable.

…

Brazil’s geography is a challenge for growth:

It has many parts completely different from each other.

Its economic core is made up of rugged terrain that needs a massive amount of investment to make it fertile.

Most of its main cities are in small coastal plains that are not in communication with each other or their hinterlands, which limits their ability to grow and invest in infrastructure.

Without rivers, it’s forced to build roads, which are very expensive.

Even then, transportation costs are still high, so the country can’t build capital.

The result is that those developing the country are those with capital, which leads to economic inequality.

Since they didn’t need skilled labor, and they created corporate plantations as opposed to cities, Brazilians in general are poorly educated to this day.

Lack of quality land, good infrastructure, capital, and skilled labor means every time the country grows, inflation soars.

The different regions of this rugged country, plus the oligarchic nature of the economy, mean that political unity has been hard.

Curiosities of the week

Hot takes

No hot takes for this week, letting them incubate first…

Open questions

How to evaluate a country’s opportunity set for growth? Some of my HKS friends are taking courses on identifying “binding constraints” for a country. The logic is that we can evaluate input-output relationship of factors of production and economic growth. Examples: if capital supply is scarce, we would expect capital-intensive sectors to be not growing. If highly-educated labor supply is scarce, we would expect sectors like tech (intensive in human capital) to be not growing. Misdiagnosing root cause of growth constraint may lead to misallocation of resource in trying to unblock growth. I am interested to see a comprehensive study on this (for any example country).

Books / papers

Geopolitical Alpha: An Investment Framework for Predicting the Future - thesis of the book is that policy-makers’ material constraints dictate their decision-making more than their stated preferences, and those constraints have hierarchy, starting from the strongest to the weakest: politics > economics / finance > geopolitics > constitutional/legal.

Graphs / charts / tables / maps

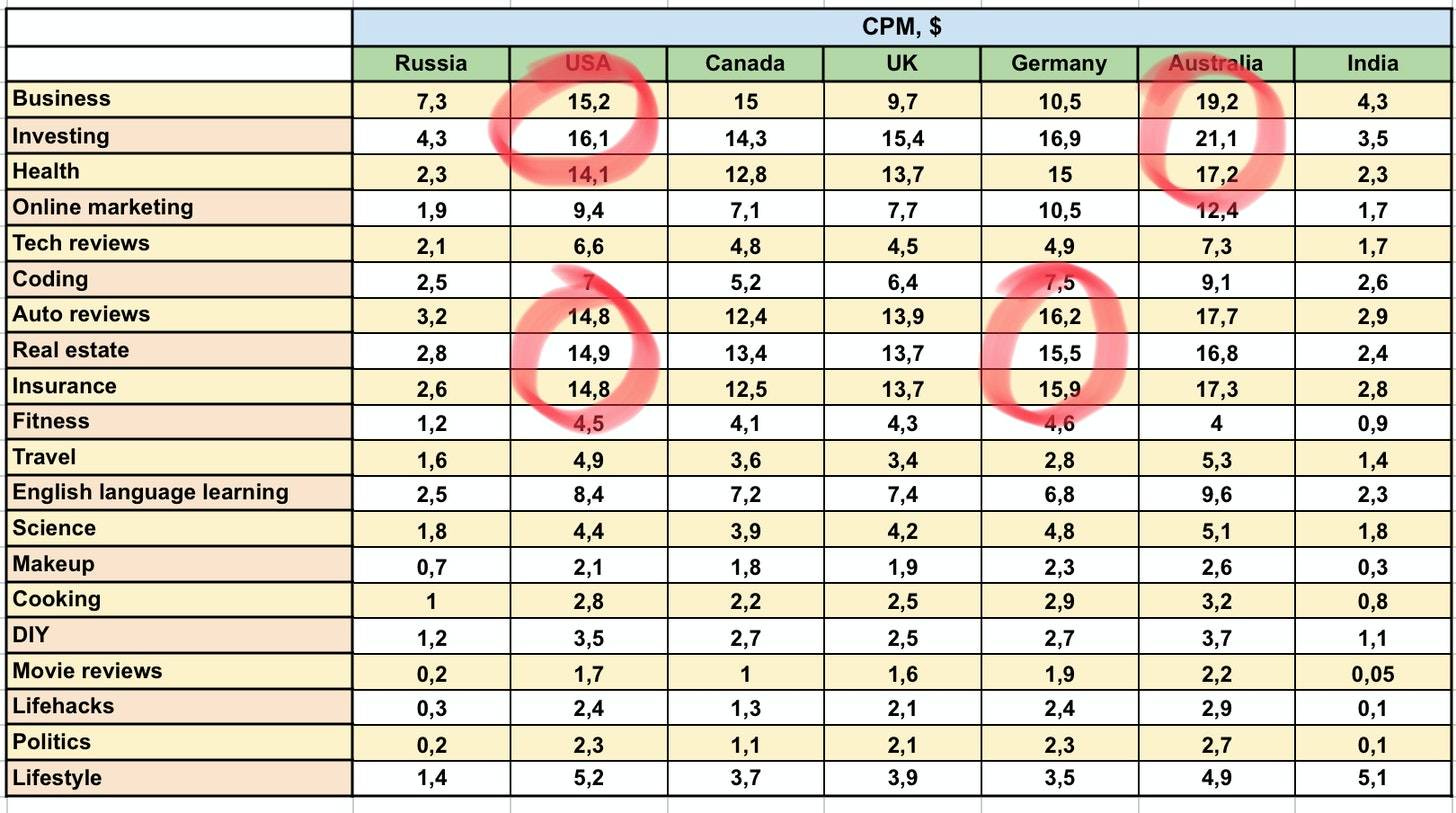

CPM of developed market vs emerging market

YouTube’s CPM (cost per mille, or cost per thousand) for audience in each niche vary wildly between developed countries and emerging countries. India’s CPM is 2-5x smaller vs its developed countries’ counterparts. Maybe Indonesia have similar CPM with India. This means to generate similar advertising revenue, a creator need to reach out to 2-5x more audience, which incentivise “dumbing down” their content to ensure the broadest appeal (Exhibit A: Atta Halilintar, etc.). Creators in developing market may need to monetize their audience base better and earlier (e.g., developing product line to push againt captive audience, etc.) vs only relying on advertising revenue.